Genitive: Aquarii

Abbreviation: Aqr

Size ranking: 10th

Origin: One of the 48 Greek constellations listed by Ptolemy in the Almagest

Greek name: Ὑδροχόος (Hydrochoös)

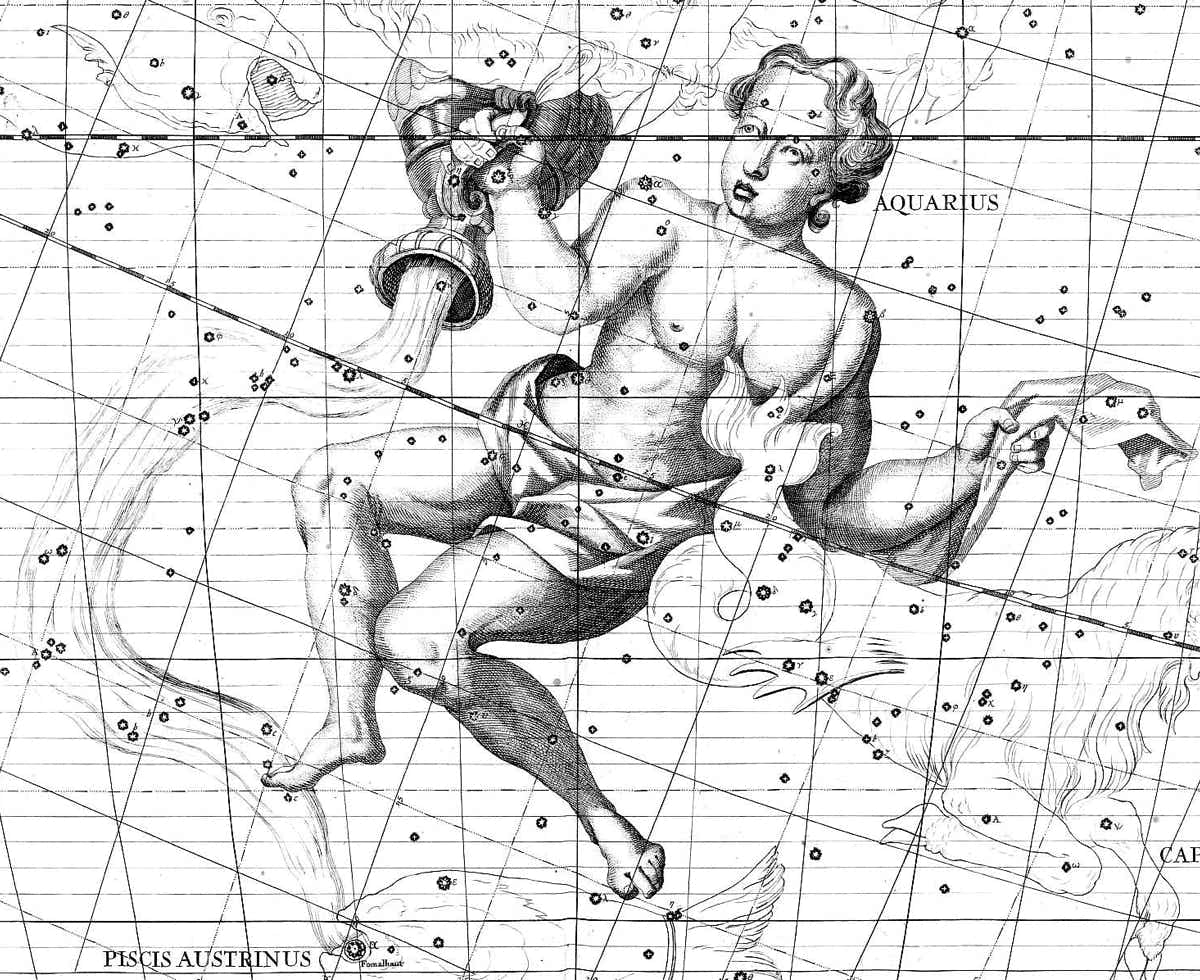

Star maps show Aquarius as a young man pouring water from a jar or amphora, although Ovid, in his Fasti, says the liquid is a mixture of water and nectar, the drink of the gods. The water jar is marked by a Y-shaped asterism of four stars centred on 4th-magnitude Zeta Aquarii, and the stream ends in the mouth of the Southern Fish, Piscis Austrinus. Who is this young man commemorated as Aquarius?

The most popular identification is that he is Ganymede or Ganymedes, said to have been the most beautiful boy alive. He was the son of King Tros, who gave Troy its name. One day, while Ganymede was watching over his father’s sheep, Zeus became infatuated with the shepherd boy and swooped down on the Trojan plain in the form of an eagle, carrying Ganymede up to Olympus (or, according to an alternative version, sent an eagle to do it for him). The eagle is commemorated in the neighbouring constellation of Aquila. As compensation for spiriting away his son, Zeus presented King Tros with a pair of fine horses, although some writers said the gift was a golden vine.

In another version of the myth, Ganymede was fought over by two rival admirers: he was first carried off by Eos, goddess of the dawn, who had a passion for young men, but was then stolen from her by omnipotent Zeus.

Either way, Ganymede became wine-waiter to the gods of Olympus, dispensing nectar from his bowl, to the annoyance of Zeus’s wife Hera. Robert Graves tells us that this myth became highly popular in ancient Greece and Rome where it was regarded as signifying divine endorsement for homosexuality. The Latin translation of the name Ganymede, Catamitus, gave rise to the word catamite.

If this myth seems insubstantial to us, it is perhaps a result of the Greeks imposing their own story on a constellation they adopted from elsewhere. The constellation of the water pourer originally seems to have represented the Egyptian god of the Nile – but, as Robert Graves notes, the Greeks were not much interested in the Nile.

Germanicus Caesar identifies the constellation with Deucalion, son of Prometheus, one of the few men to escape the great flood. ‘Deucalion pours forth water, that hostile element he once fled, and in so doing draws attention to his small pitcher’, wrote Germanicus. Hyginus offers the additional identification of the constellation with Cecrops, an early king of Athens, seen making sacrifices to the gods using water, for he ruled in the days before wine was made.

Stars of Aquarius

The constellation’s name in Greek was Ὑδροχόος, i.e. Hydrochoös. In the Almagest, Ptolemy described the stars Alpha, Beta, and Gamma Aquarii as lying in the right shoulder, left shoulder, and the right forearm of the figure respectively. The head of Aquarius is marked by the relatively lowly 25 Aquarii, of 5th magnitude.

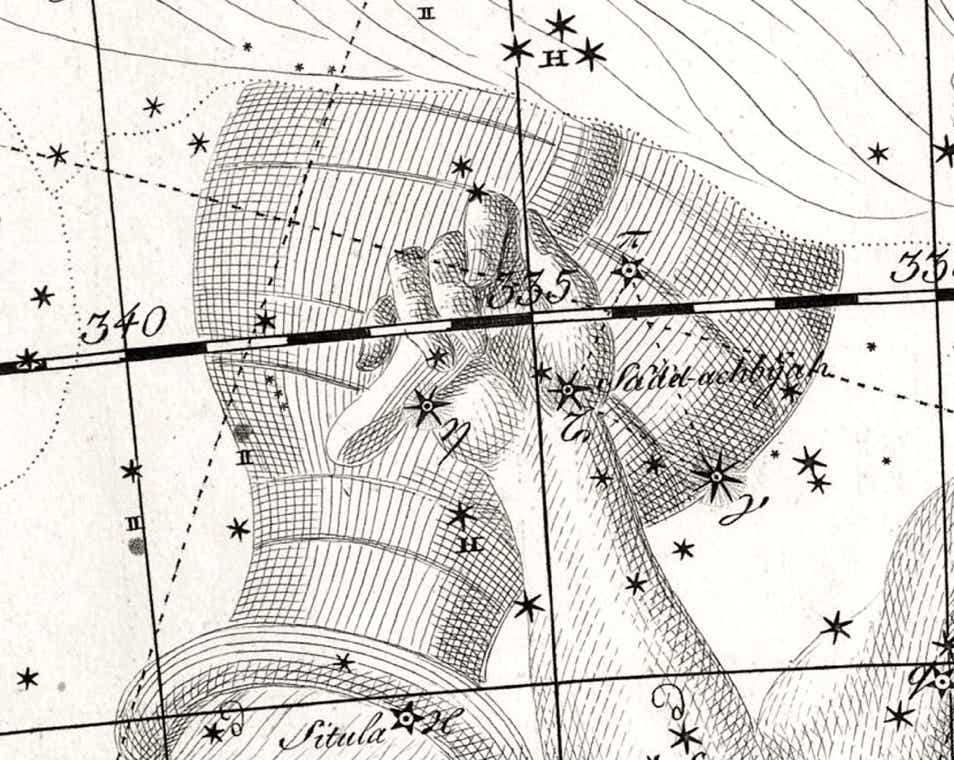

Several stars in Aquarius have names beginning with ‘Sad’. The Arabic word sa'd is usually said to mean ‘luck’ or ‘lucky’, but has also been translated as good fortune, auspicious, an omen, or blessedness. There were ten Arabic asterisms bearing the name sa'd, stretching from Pegasus southwards through Aquarius and into Capricornus. All but one of these asterisms consisted of two stars, the exception being the water-jar asterism of four stars (Gamma, Zeta, Eta, and Pi Aquarii) which the Arabs knew as sa’d al-akhbiya. In a major study of Arabic star lore, Danielle Adams of the University of Arizona has translated this name as ‘the auspice of woollen tents’, the Y-shaped arrangement of stars perhaps being reminiscent of a tent. Gamma Aquarii, the brightest star in this asterism at magnitude 3.8, is known as Sadachbia, from the Arabic name sa’d al-akhbiya.

Alpha Aquarii, magnitude 2.9, is called Sadalmelik, from sa’d al-malik, ‘the auspice of the king’. Beta Aquarii, also magnitude 2.9, is Sadalsuud, from sa’d al-su’ud, ‘the auspice of auspices’ (although the German expert on star names, Paul Kunitzsch, translates this as ‘luckiest of the lucky’). The exact significance of these names has long been lost even by the Arabs, according to Kunitzsch.

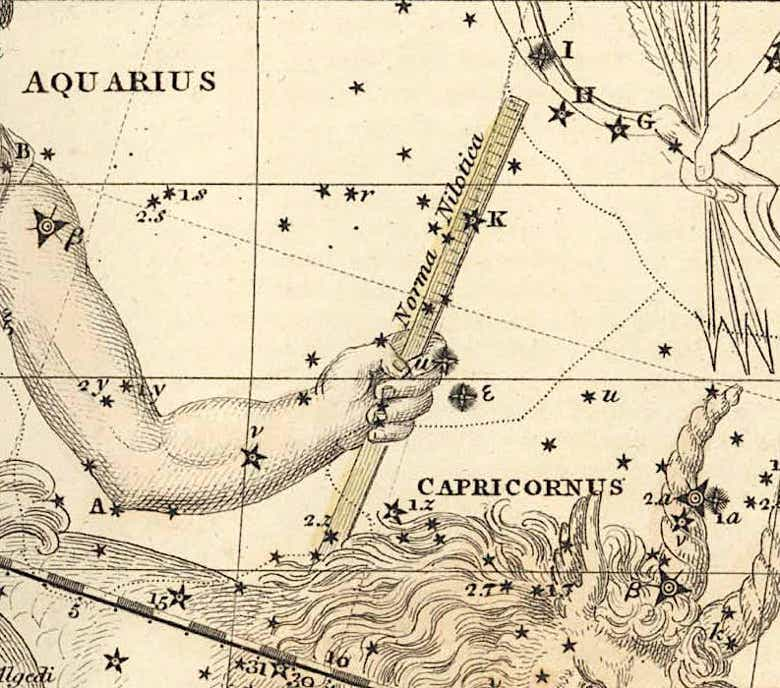

On his Celestial Atlas of 1822 the Scottish schoolmaster Alexander Jamieson introduced a new sub-constellation, Norma Nilotica, a rod for measuring the depth of the Nile, held in the left hand of Aquarius. This reappeared on the set of constellation cards called Urania’s Mirror in 1825 and was adopted by the American astronomer Elijah Hinsdale Burritt (1794–1838) on his popular Atlas Designed to Illustrate The Geography of the Heavens (1835 and many subsequent editions), but was otherwise ignored.

The Water

Ptolemy listed 20 stars as lying in the flow of water from the jar, almost as many stars as in the main figure of Aquarius itself – see, for example, Albrecht Dürer’s celestial chart of 1515. In fact, early writers such as Aratus, Eratosthenes, and Geminus regarded the Water (Hydor, Ὕδωρ) as either a separate constellation or a sub-constellation within Aquarius. The flow of water started at the star we know as Kappa Aquarii and ended at the first-magnitude star we call Fomalhaut, in the mouth of the southern fish, Piscis Austrinus. This is another example of stars being shared between constellations in the days before rigorous boundaries were established. Fomalhaut is now the exclusive property of the neighbouring Piscis Austrinus.

Ptolemy listed three other ‘unformed’ stars that formed a triangle near the flow of water; these have since been transferred across the border into neighbouring Cetus and are now known as 2, 6, and 7 Ceti.

Chinese associations

Many ancient Chinese constellations, big and small, were to be found in the area of sky now occupied by Aquarius, including three after which lunar mansions were named. The 10th Chinese lunar mansion, Nü (‘girl’), took its name from a group near the border with Aquila formed by Epsilon, Mu, 4, and 3 Aquarii, representing a maidservant. Beta Aquarii and Alpha Equulei formed Xu (‘emptiness’), the 11th lunar mansion, symbolizing a place of desolation and darkness connected with funerals and mourning.

The present-day Alpha Aquarii was joined with Theta and Epsilon Pegasi to form a V-shape, like the pitched roof of a building, called Wei, ‘rooftop’. There are in fact three Chinese constellations whose names are Romanized as Wei, and each has a different meaning. This Wei is the one after which the 12th lunar mansion is named. (The other two are in Aries and Scorpius.)

In the north of Aquarius, the Water Jar asterism consisting of Gamma, Pi, Zeta, and Eta Aquarii was known as Fenmu, a burial place or tomb. South of it, a line of four stars including Kappa Aquarii formed Xuliang, representing a mausoleum, apparently for departed Emperors. Two other small constellations in this same area continued the theme of death and mourning, namely Qi, ‘weeping’, and Ku, ‘crying’, each consisting of two stars. Another two stars in northern Aquarius, identities uncertain, were Siming, a deity governing punishment, life, and death.

Crossing Aquarius from southern Pisces into Capricornus was the extensive constellation Leibizhen, a line of 12 stars including Phi, Lambda, Sigma, and Iota Aquarii. This represented a chain of fortifications to protect the army camp or barracks to the south. The camp was the quarters for Yulinjun, the Imperial (or Royal) Guards, fearsome soldiers said to have been drafted from the northern territories. Yulinjun was a sprawling group of 45 stars, the greatest number of stars in any Chinese constellation, most of them in Aquarius but a handful farther south in Piscis Austrinus.

Straddling the border with Capricornus was Tianleicheng, a group of 13 stars including Xi and Nu Aquarii, representing a castle with earthwork ramparts (although some interpretations place Tianleicheng in Piscis Austrinus). Another figure whose location is disputed is Fuyue, an axe used for executions or for cutting crops. According to one interpretation this consisted of three stars near the border with Cetus but others have placed it not in Aquarius at all but farther south in Sculptor.

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved

Aquarius and his water jar, from the Atlas Coelestis of John Flamsteed (1729). The flow of water from the jar extends into the mouth of the southern fish, Piscis Austrinus, and ends at the bright star Fomalhaut, which Ptolemy regarded as being common to both constellations.

The water jar asterism of Aquarius consists of the four stars Gamma (lower right), Zeta (centre), Eta (left), and Pi Aquarii (top), seen here on Chart XVI of Johann Bode’s Uranographia. Bode used the name Sa’d el-achbijah for the central star, Zeta, on the palm of the water carrier’s hand, but that name is now applied to Gamma Aquarii, with the amended spelling Sadachbia. Kappa Aquarii, on the lip of the jar, marks the start of the flow of water. Here it is named Situla, a Latin word referring to a bucket or pail.

The ten Auspicious asterisms, with translations according to

Danielle Adams of the University of Arizona:

η and ο Pegasi, The Auspice of Rain (sa’d matar);

μ and λ Pegasi, The Auspice of the Exalted One (sa’d al-bari’);

ζ and ξ Pegasi, The Auspice of the Aspiring One (sa’d al-humam);

θ and ν Pegasi, The Auspice of Lambs (sa’d al-baha’im);

γ, ζ, η, and π Aquarii, The Auspice of Woollen Tents (sa’d al-akhbiya);

α and ο Aquarii, The Auspice of the King (sa’d al-malik);

β and ξ Aquarii, The Auspice of Auspices (sa’d al-su’ud);

γ and δ Capricorni, The Scattering Auspice (sa’d nashira);

μ and ε Aquarii, The Voracious Auspice (sa’d bul’);

α and β Capricorni, The Auspice of the Slaughterer (sa’d al-dhabih).

Norma Nilotica, a measuring rod for the Nile held by Aquarius, on Plate 21 of Alexander Jamieson’s Celestial Atlas. Its brightest star was 4th-magnitude 3 Aquarii, labelled K on the chart.

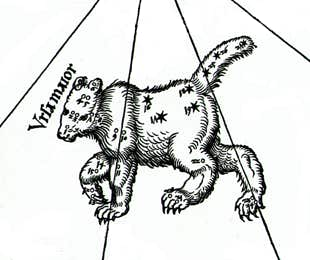

Aquarius and the flow of water as depicted by Albrecht Dürer on his northern celestial hemisphere chart of 1515. The positions and magnitudes of the stars were taken from Ptolemy’s catalogue in the Almagest, and they were numbered according to Ptolemy’s listing. Ptolemy described stars 23 to 42 as lying ‘on the flow of water’. The southernmost of them, number 42, is the one we know as Fomalhaut, which at that time was shared between Aquarius and Piscis Austrinus. In his outstretched hand the water carrier holds a cloth, presumably for mopping up spillages. Note the mis-spelling of Aquarius as ‘Aquaruis’, partially rescued by the dot over where the i should have been. Dürer drew the constellations in mirror image, as they would appear on a celestial globe, so the figure is reversed from the way we see it in the sky.